Have you ever looked at a world map and noticed how the continents seem to fit together like a giant puzzle? The coastlines of South America and Africa, for example, appear to be a near-perfect match. This observation, among others, was the foundation of the Continental Drift Theory (CDT), proposed by German geophysicist Alfred Wegener in the 1920s.

The Core Idea 🌍

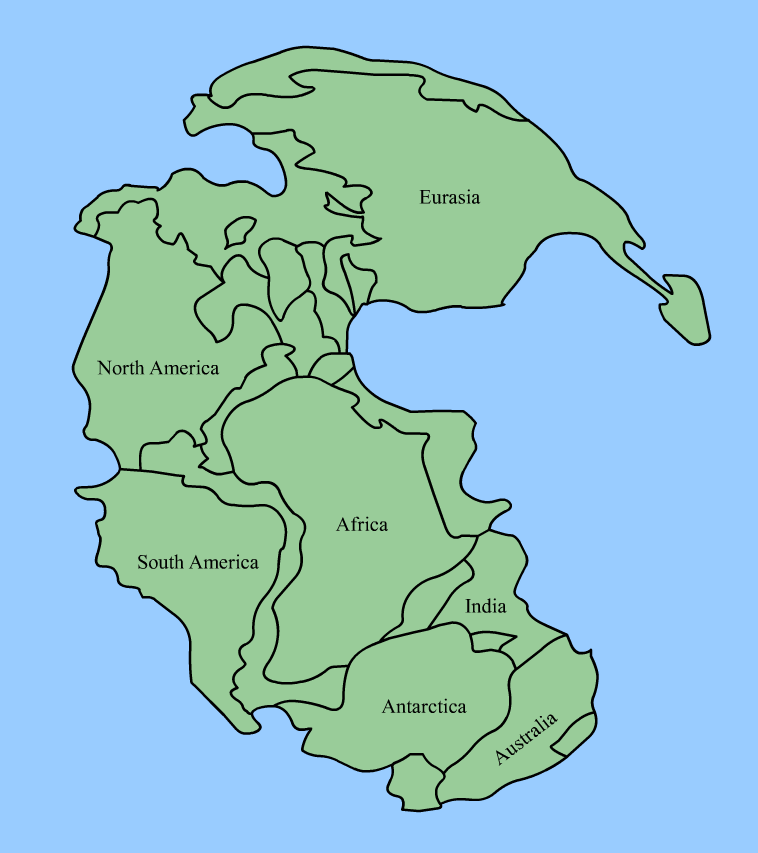

Wegener’s theory suggests that about 250 million years ago (in the Permian period), all the world’s landmasses were joined into a single supercontinent he called Pangaea, meaning “all lands.” This massive continent was surrounded by a single global ocean named Panthalassa. About 200 million years ago (Mesozoic Era), Pangaea began to break apart. A sea called Tethys Sea divided Pangaea into two smaller supercontinents: Laurasia to the north and Gondwanaland to the south. Over millions of years, these landmasses continued to drift and fragment, slowly moving to their present-day positions.

Evidence for Continental Drift

Wegener didn’t just propose his theory; he gathered a variety of evidence to support it. The main points he presented are compelling and span multiple fields of science.

1. Apparent Affinity of Physical Features

This is the “jigsaw puzzle” fit. The coastlines of continents, especially South America and Africa, show remarkable similarities, suggesting they were once joined.

2. Botanical Evidence 🌿

The presence of the same plant fossils across different continents provides strong support for the theory. For instance, Glossopteris, a seed fern, is found in Carboniferous rocks in India, Australia, South Africa, the Falkland Islands, and Antarctica. The widespread distribution of this ancient vegetation is easily explained if these landmasses were once connected. While some critics argue that similar vegetation is found in northern regions like Afghanistan and Siberia, the concentrated distribution across the Southern Hemisphere remains a key piece of evidence.

3. Distribution of Fossils 🦕

The discovery of identical animal fossils on continents now separated by vast oceans is another powerful argument. For example, skeletons of the freshwater reptile Mesosaurus have been found only in South Africa and Brazil. These two locations are currently over 4,800 km apart, separated by the Atlantic Ocean, making it nearly impossible for the small, non-marine reptile to have crossed it. Another example is the fossil of the land reptile Lystrosaurus, found in Africa, India, and Antarctica.

4. Rocks of Same Age Across the Oceans

Geological evidence also supports the theory. Ancient rock belts of the same age and composition are found on opposing coasts. The 2,000-million-year-old rocks on the Brazilian coast, for example, perfectly match those on the western coast of Africa.

5. Tillite Deposits

Tillite is a sedimentary rock formed from glacial deposits. The Gondwana system of sediments in India has thick tillite layers at its base, indicating extensive glaciation. Counterparts of these deposits are found in Africa, the Falkland Islands, Madagascar, Antarctica, and Australia. The presence of these glacial deposits on continents that are now in tropical or temperate zones provides unambiguous evidence of significant climate change and continental movement.

6. Placer Deposits

Rich placer deposits of gold are found on the Ghana coast in West Africa. However, the source of these gold-bearing veins is in Brazil. This suggests that when Africa and South America were side-by-side, the deposits were part of a single, continuous geological formation.

The Flaw of Continental Drift Theory: What Caused the Drift?

Despite the compelling evidence, Wegener’s theory faced significant criticism. The main weakness was his inability to explain the mechanism or “force” behind the continental drift. He suggested two forces: a pole-fleeing force (due to the Earth’s rotation) and tidal force (from the sun and moon). Both of these forces were later proven to be far too weak to move continents. This lack of a plausible driving force caused the scientific community to largely reject his theory for several decades. It wasn’t until the development of the theory of Plate Tectonics in the mid-20th century, which introduced the concept of seafloor spreading and mantle convection, that the mystery of the drifting continents was finally solved.

The explanation was given by the Convectional Current Theory by Arthur Holmes