Where is the Strait of Hormuz Located?

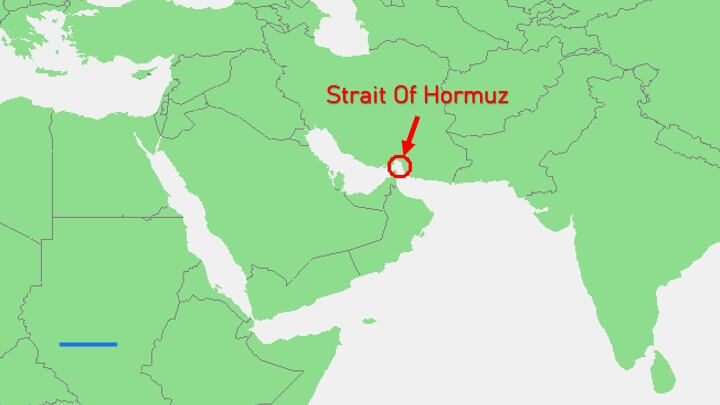

The Strait of Hormuz is a narrow, strategically vital waterway connecting the Persian Gulf to the Arabian Sea and, by extension, the wider Indian Ocean. Flanked by Iran to the north and the Musandam Governorate of Oman and the United Arab Emirates to the south, it is arguably the world’s most critical maritime chokepoint, through which a significant portion of the globe’s energy supplies transit.

Geographical Significance

The Strait of Hormuz is approximately 90 nautical miles (167 km) long. Its width varies from about 52 nautical miles (96 km) to a mere 21 nautical miles (39 km) at its narrowest point. The navigable shipping lanes are even more restricted, extending only about two miles in each direction, with a two-mile-wide median separating them. This geographical constriction, combined with the immense volume of traffic, makes it highly vulnerable to disruptions. To manage the flow and minimise collision risks, ships follow a Traffic Separation Scheme (TSS) under the transit passage provisions of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea.

Economic Importance

The economic significance of the Strait of Hormuz cannot be overstated. It serves as the primary maritime artery for oil and gas exports from major producers in the Persian Gulf, including Saudi Arabia, Iraq, the UAE, Qatar, Iran, and Kuwait.

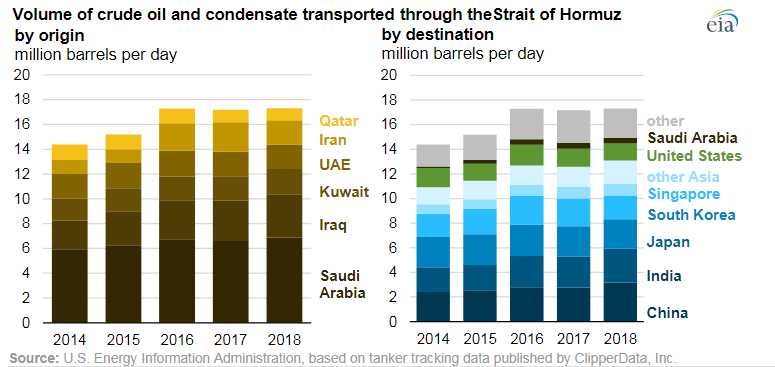

- Oil Transit: Approximately one-fifth of the world’s total oil consumption, or about 20-21 million barrels per day, passes through the Strait of Hormuz. This represents a substantial portion of global seaborne oil shipments.

- LNG Transit: In addition to oil, a significant amount of liquefied natural gas (LNG) also transits the Strait, accounting for roughly one-third of the global LNG trade.

- Asian Dependency: The overwhelming majority (over 80%) of crude oil and condensate exports passing through the Strait are destined for Asian markets, with China, India, Japan, and South Korea being the largest recipients. For countries like India, which imports approximately 90% of its crude oil, with over 40% originating from Middle Eastern nations, the Strait is an existential trade route.

Any disruption to the free flow of energy through this waterway has immediate and severe implications for global energy security, prices, and supply chains.

Volume of crude oil and condensate transported through the Strait of Hormuz from 2014 to 2018

How has it become a Global Geopolitical Chokepoint?

The Strait of Hormuz has long been a focal point of geopolitical tensions, particularly concerning Iran’s strategic position. Iran has repeatedly threatened to close or disrupt shipping in the Strait in response to perceived threats or sanctions from the United States and its allies.

Current Situation (June 2025): The geopolitical landscape surrounding the Strait of Hormuz is currently highly volatile. Following recent US strikes on Iranian nuclear facilities, Iran’s Parliament has reportedly approved a decision to close the Strait of Hormuz. While the final decision rests with Iran’s Supreme National Security Council, this move underscores Iran’s willingness to weaponise its geographical advantage in response to escalating tensions.

- Iranian Leverage: Iran possesses the capability to hinder shipping through various means, including naval blockades, mines, and drone attacks. While a full closure would be counterproductive to Iran’s own oil exports, even partial disruptions can send global oil prices skyrocketing and destabilise markets.

- Global Impact: A complete blockage, even temporary, could cut global oil supplies by a substantial margin, potentially exceeding the impact of historical disruptions like the 1979 Iranian revolution. This would have profound economic ramifications worldwide, particularly for energy-dependent Asian economies.

- Security Concerns: The recent collision of two oil tankers near the Strait, alongside reports of spotty navigation signals and increased wariness among shipowners, highlights the fragility of maritime security in the region amidst heightened conflict.

Implications for Global Powers

- United States: The U.S. Fifth Fleet maintains a significant presence in the region to ensure freedom of navigation and deter any attempts to close the Strait. Any Iranian move to block the waterway would likely be met with a robust international response.

- Asian Economies: Countries like China, India, Japan, and South Korea are particularly vulnerable to disruptions in the Strait due to their heavy reliance on Middle Eastern oil and gas imports. While some diversification of energy sources is ongoing (e.g., India’s increased imports from Russia via alternative routes), a closure would still necessitate a scramble for alternatives, driving up costs and destabilising supply chains.

- Oil Markets: The threat of disruption alone can cause significant fluctuations in global oil prices. A prolonged closure would lead to a severe supply shock, potentially pushing Brent crude prices to unprecedented levels.

The Strait of Hormuz remains a critical artery for global energy trade and a persistent flashpoint in international relations. Its narrow confines and strategic location grant Iran significant leverage in regional geopolitics, particularly during periods of heightened tension. As the world navigates complex geopolitical dynamics and the ongoing need for energy security, the stability of the Strait of Hormuz will continue to be a paramount concern for governments and markets worldwide.

What are the alternatives to the Strait of Hormuz?

While the Strait of Hormuz is the primary and most efficient route for oil and gas exports from the Persian Gulf, there are some existing and proposed alternatives, primarily in the form of pipelines. However, these alternatives have limited capacity and cannot fully replace the immense volume of oil and gas that transits the Strait.

1. Pipelines Bypassing the Strait:

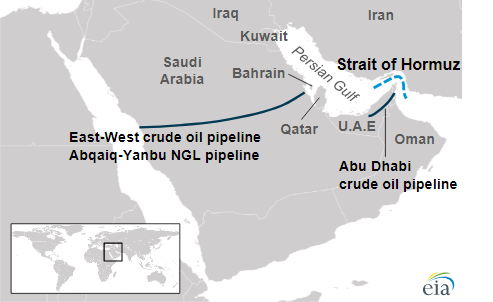

- Saudi Arabia’s East-West Pipeline (Petroline): This is the most significant existing alternative. It runs from the Abqaiq oil processing centre near the Persian Gulf to the Red Sea port of Yanbu. It has a design capacity of 5 million barrels per day (b/d) and has been temporarily expanded to 7 million b/d. In times of disruption around the Strait of Hormuz, Saudi Arabia can pump more crude through this pipeline to ports on the Red Sea, from where it can then be shipped to global markets. However, it rarely operates at full capacity, leaving some spare capacity for diversion.

- UAE’s Abu Dhabi Crude Oil Pipeline (ADCOP): This pipeline connects onshore oil fields in Abu Dhabi to the Fujairah export terminal on the Gulf of Oman, effectively bypassing the Strait of Hormuz. It has a capacity of around 1.5 to 1.8 million b/d. The UAE has also built significant oil storage facilities at Fujairah.

- Iran’s Goreh-Jask Pipeline: Iran itself has built a pipeline from Goreh to the Jask export terminal on the Gulf of Oman, aiming to provide an alternative export route that avoids the Strait of Hormuz. It was inaugurated in 2021 with an effective capacity of around 300,000 b/d, but its usage has been inconsistent.

- Iraqi Pipelines: While some Iraqi pipelines exist, such as the Iraqi Pipeline through Saudi Arabia (IPSA), many have faced operational issues or political closures in the past. There are also proposals for pipelines from Iraqi Kurdistan to Turkey (to the port of Ceyhan), which would bypass the Gulf entirely.

Limitations of Pipeline Alternatives:

- Limited Capacity: Even collectively, the existing bypass pipelines can only handle a fraction of the 20-21 million b/d that typically transits the Strait of Hormuz. A complete closure would still result in a significant global supply shock.

- Cost and Time: Expanding pipeline capacity is a costly and time-consuming endeavour, making it unsuitable for immediate responses to disruptions.

- Geopolitical Vulnerability: These pipelines can also be targets of attack or political leverage, as seen with past disruptions to various regional pipelines.

2. Longer Maritime Routes (Less Practical for Most Persian Gulf Oil):

For oil that originates within the Persian Gulf, there are no practical alternative sea routes that completely bypass the Strait without using existing pipeline infrastructure to move it to another coast first.

- Round Africa (Cape of Good Hope): For shipments destined for Europe or the Americas, vessels could theoretically bypass the Red Sea/Suez Canal and sail around the Cape of Good Hope. However, this dramatically increases transit time and shipping costs, making it highly uneconomical for regular operations from the Persian Gulf. This route is more relevant as an alternative for vessels transiting the Suez Canal if the Bab al-Mandeb Strait (at the entrance to the Red Sea) is disrupted.

.png)

What is at stake for Europe if the Strait of Hormuz is blocked?

Europe has significant stakes due to its energy dependencies, economic stability, and broader geopolitical interests. For Europe, the Strait of Hormuz is not just about direct energy imports but about global energy market stability, economic resilience, and regional security. A significant disruption would be, as one former French intelligence officer put it, “a disaster for Europe.”

Here’s what’s at stake for Europe:

- Energy Security and Supply Disruptions:

- Oil and LNG Imports: Despite efforts to diversify away from Russian energy, Europe still relies on Gulf nations, particularly Saudi Arabia, Qatar, and the UAE, for substantial portions of its oil and Liquefied Natural Gas (LNG) supplies. Much of this energy travels through the Strait of Hormuz. A blockade would directly impact these imports, leading to immediate shortages.

- Refined Products: Europe is also a significant importer of refined products like diesel and jet fuel from the Middle East. For instance, in 2024, over 20% of diesel imported by the EU, UK, and Norway originated from Gulf countries, and more than half of Europe’s jet fuel imports came from the region. Disruptions would severely affect transportation, industry, and travel across the continent.

- Tight Energy Market: Europe is still recovering from the energy crisis triggered by the Russia-Ukraine conflict and sanctions on Russian energy. Its gas stockpiles, though replenished, are vulnerable. A disruption in the Strait would exacerbate this fragility, putting immense pressure on supply and prices.

- Soaring Energy Prices and Inflation:

- Global Price Impact: Even if Europe isn’t the primary direct recipient of all oil transiting the Strait, a closure would cause global oil and gas prices to skyrocket. This is because approximately 20% of the world’s daily oil consumption and a significant portion of global LNG pass through this chokepoint.

- Economic Blow: Such a price surge would fuel inflation across Europe, impacting core industries like manufacturing, transportation, and agriculture. Consumers would face higher costs for fuel, electricity, and goods, potentially triggering an economic slowdown or even a recession. The nascent economic recovery in many European countries is highly fragile and vulnerable to such a shock.

- Supply Chain Disruptions and Increased Costs:

- Trade Routes: Beyond energy, the Strait of Hormuz is a vital route for international trade. Disruptions to shipping would cause delays in critical imports and exports, further straining global supply chains.

- Shipping Costs: Maritime insurance premiums would spike, and vessels might be forced to take longer, more expensive alternative routes (e.g., around the Cape of Good Hope if the Red Sea/Suez Canal route is also affected by regional instability). These increased costs would be passed on to European businesses and consumers.

- Geopolitical Instability and Security Concerns:

- Regional Escalation: A blockade or significant disruption in the Strait of Hormuz would be an act with severe international consequences, almost certainly leading to a robust military response from the United States and its allies. This would risk a major escalation of conflict in the Middle East, a region already prone to instability.

- NATO Involvement: A prolonged blockade could draw EU navies and potentially NATO into the conflict, raising the prospect of direct military engagement and further destabilising the wider region. This would divert resources and attention from other pressing geopolitical challenges.

- Refugee Flows: Increased conflict and instability in the Middle East could also lead to new waves of refugees and migrants, posing further challenges for European countries.