Human settlements are places where people live together in a more or less permanent way. These communities can range in size and complexity, from small villages focusing on agriculture to massive metropolitan cities with diverse economic activities.

‘Human Settlement means clusters of dwellings of any type or size where human beings live.’ (NCERT)

The basic unit of human civilisation is the family. When humans decide to form families and make a home it forms the basis of any settlement. Multiple houses form clusters and the same are called settlements. The arrangement of these houses in the geographic landscape further defines these settlements as geography also governs the economic landscape of the region.

The United Nations, through various conferences and documents, has provided definitions and frameworks regarding human settlements. One of the key references is the Habitat Agenda, which was adopted by the United Nations Conference on Human Settlements (Habitat II) in 1996.

The United Nations defines human settlements as the totality of the human community – whether city, town, or village – with all the social, material, organizational, spiritual, and cultural elements that sustain it.

This definition encompasses not only the physical structures, such as houses, buildings, roads, and bridges but also the community and its socio-economic aspects. It includes all aspects of living environments created by humans, with an emphasis on sustainable development, living conditions, and quality of life.

The most basic classification of settlements is into rural and urban categories based on occupation:

- Rural Settlements: These are areas where most of the people are engaged in primary activities like agriculture, forestry, mining, and fishery. They are characterised by vast open spaces, green environments, and a close-knit community structure.

- Urban Settlements: Urban areas are characterised by secondary and tertiary activities such as manufacturing and services. They are typically more densely populated and have a more complex social structure than rural settlements.

‘Ekistics’ by C. A. Doxiadis

C. A. Doxiadis’s “Ekistics” refers to a proposed interdisciplinary field aimed at understanding and improving human settlements.

Constantinos Apostolou Doxiadis, a Greek architect, planner, and visionary, introduced this term in the mid-20th century. The term ‘Ekistics’ derives from the Greek word ‘oikistikos’, which means ‘settled’ or ‘relating to the establishment of a house or home’.

Ekistics is grounded in the belief that understanding the complex interactions between human beings and their living environments is crucial for creating functional and sustainable settlements. This approach encompasses not only architecture and urban planning but also integrates insights from sociology, ecology, economics, psychology, and anthropology.

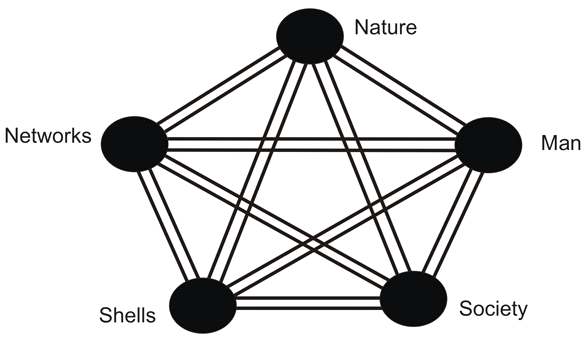

The diagram shows how each element—Nature, Man, Society, Shells (representing buildings and infrastructure), and Networks (representing communication and transportation)—is connected to all the others, suggesting a complex web of relationships that underpin the function and structure of human habitats.

Five Principles Guiding Settlement Formation as described by C. A. Doxiadis

- Maximization of Contacts: This principle emphasizes the importance of increasing potential contacts with elements of nature, other people, and man-made structures. It is akin to an operational definition of personal human freedom, reflecting the human tendency to expand their environment and interactions.

- Minimization of Effort: According to this principle, the structures and paths within a settlement should be designed to require the minimum effort for achieving actual and potential contacts. This includes designing floors to be horizontal or selecting routes that are most efficient.

- Optimization of Protective Space: This involves selecting an optimal distance from others to maintain contact without sensory or psychological discomfort. It accounts for personal space and privacy needs, which can be represented physically through clothing, the layers of air surrounding us, and the walls of buildings.

- Optimization of the Quality of Relationships with the Environment: This principle aims to create a harmonious balance between individuals and their environment, including nature, society, buildings (shells), and networks. It involves considerations of order, physiological comfort, and aesthetics, affecting architecture and, to an extent, art.

- Synthesis of Principles: The final principle is the organization of settlements to achieve an optimum synthesis of the other four principles, contingent on time, space, actual conditions, and man’s ability to create a synthesis. A successful human settlement is one that has achieved a balance between man and the man-made environment by adhering to all five principles.

Morphogenesis of settlements by C. A. Doxiadis

Morphogenesis of settlements in the concept of Ekistics, as articulated by C. A. Doxiadis, is the study of the forces and processes that shape the form and structure of human settlements over time. It takes into account the evolution from the earliest forms of human habitation to the complex urban environments we see today.

The morphogenetic process is influenced by various forces that are both derived from human needs and the direct impact of natural elements. For example, in examining the formation of a room (referred to as the No. 2 unit in Ekistics), it is observed that rooms tend to evolve towards having flat floors, vertical orthogonal walls, and flat roofs. This adaptation is in response to biological and structural laws, such as the need for man to lie down, rest, and move without discomfort (which echoes the principle of minimizing effort) and the efficiency in accommodating furniture and saving space when multiple rooms are built together.

As human settlements grow into larger units like neighbourhoods, cities, and metropolises, different forces come into play, and their relationships change. In larger ekistic units like a metropolis, the direct influence of the physical dimensions and senses of individual humans diminishes, while the impact of natural forces such as gravity, geographic formation, modes of transportation, and systematic organization and growth become more significant.

The forces that cause morphogenesis within each type of ekistic unit demonstrate a pattern of decline in the influences derived from man’s physical dimensions and personal energy and an increase in those derived directly from nature itself as a developing and operating system. This understanding helps in planning and developing human settlements that are responsive to both human needs and environmental factors.

C. A. Doxiadis’ Classification by Size and Character

describes the classification by size and character of human settlements as a process rooted in the walking distances that are considered acceptable for daily activities. For rural dwellers, the limit is set at one hour or 5 kilometers for horizontal movement, while for urban dwellers, it is 20 minutes or 1 kilometer. This foundational measure gives rise to the concept of a city growing in concentric circles, expanding with the advent of motor vehicles into a two-speed system and eventually into interconnected settlements, leading towards larger systems or even a universal city (ecumenopolis).

Doxiadis challenges the idea that smaller, traditional cities are suitable for contemporary life, which is deeply influenced by science and technology. Instead, he posits that new types of dynamic settlements that interconnect numerous smaller ones are more appropriate for the current era. The ongoing transformation from a city (polis) to a dynamic city (dynapolis) is driven by advancements in science and technology that have revolutionized human movement in space.

Classification of human settlements is essential to avoid confusion caused by terms like small town, big town, metropolis, city, and megalopolis, which can be ambiguous without a clear reference to size. To achieve this, Doxiadis proposes to begin with the smallest unit, the individual, and progressively scale up to the entire planet, systematically defining each unit in terms of its size and kinetic fields, for both pedestrians and motor vehicles.

Doxiadis emphasizes that without referring to size, discussing the quality of life or any significant phenomenon in human settlements is impossible. There’s an acknowledgement that the desire to return to smaller cities is often utopian, as it doesn’t account for the advantages offered by larger cities. At the same time, there is an acknowledgement that the increase in size does not inherently mean a loss in quality. Instead, there should be a focus on improving the quality of life within the larger cities, which is both desirable and realistic.

Evolution of Settlements: From Nomadic Tribes to Urban Jungles

The evolution of settlements has been a testament to human ingenuity, adaptability, and the relentless pursuit of social advancement. Let us delve into the transformative journey of human settlements, tracing the path from the nomadic wanderings of ancient tribes to the teeming metropolises that stand as pillars of modern civilization.

The Early Steps: A Shift from Mobility to Permanence (c. 10,000 BC onwards)

- Hunter-Gatherer Legacy: For millennia, humans were primarily nomadic, roaming the Earth in small bands. Their settlements were impermanent camps, strategically located near seasonal food sources like wild game and edible plants.

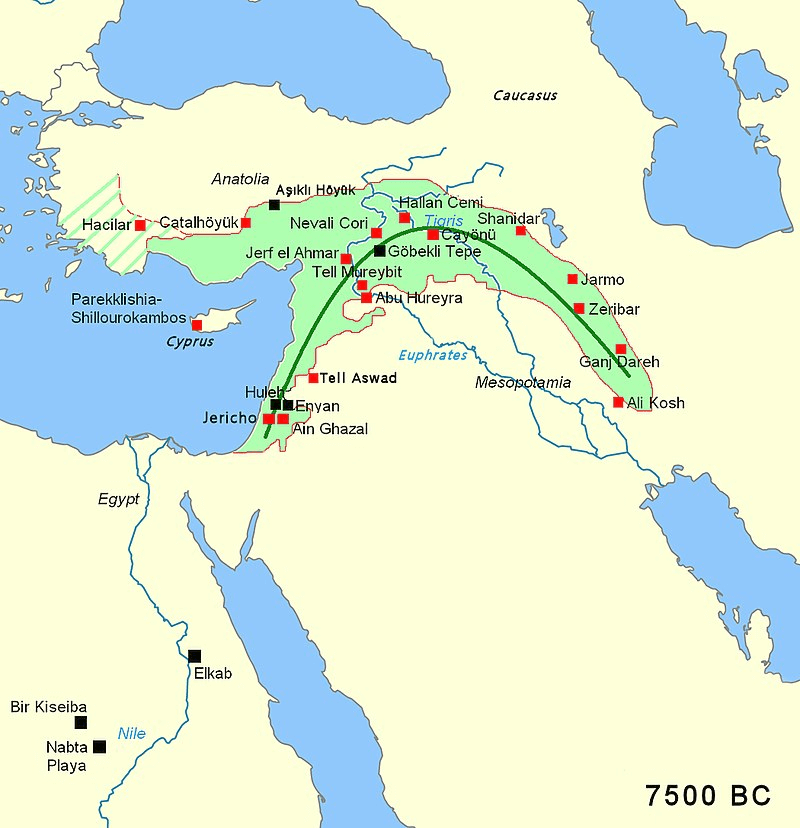

- The Agricultural Revolution: Around 10,000 BC, a pivotal shift occurred. The development of agriculture, particularly the cultivation of crops and domestication of animals enabled a more settled lifestyle. This transition is evident in archaeological sites like Çatalhöyük in modern-day Turkey and Jericho in the West Bank, showcasing permanent dwellings and evidence of food storage.

The Rise of Civilizations: From Villages to Urban Centers (c. 4000 BC onwards)

- Fertile Grounds for Urbanization: The reliable food production offered by agriculture fostered population growth and the rise of complex societies. Regions like Mesopotamia’s Fertile Crescent witnessed the emergence of the world’s first cities like Uruk and Ur.

- Cradle of Innovation: These early urban centres served as hubs for various activities beyond mere residence. They became centres of administration, facilitating trade networks and fostering cultural exchange. Notably, advancements such as writing systems, the wheel, and legal codes emerged during this period, enabling the management of resources and the establishment of social order – hallmarks of burgeoning civilizations.

Evolving Landscapes: Diverse Expressions of Settlements (3000 BC – 15th Century AD)

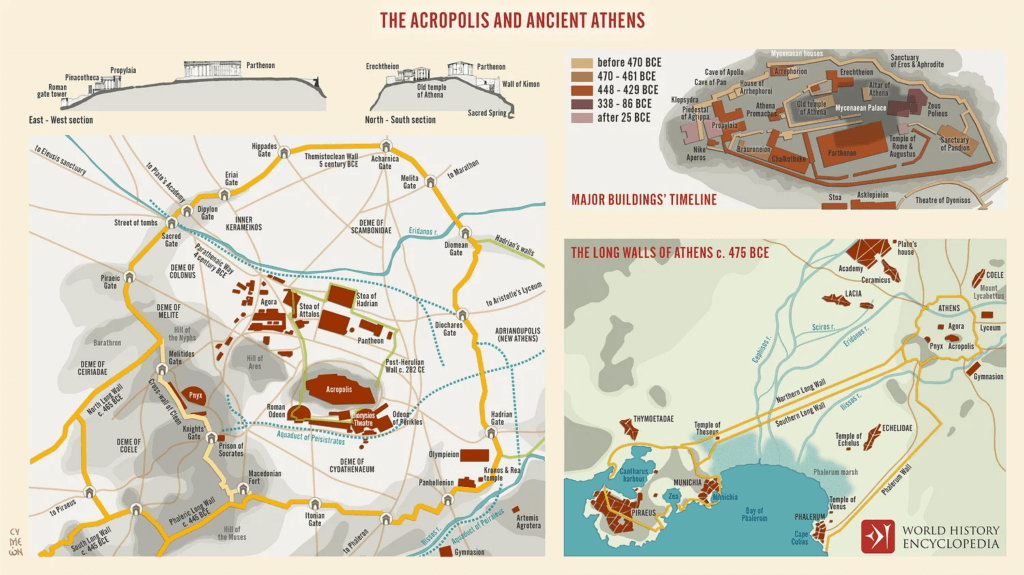

- The Classical World: As empires rose and fell, the concept of settlements continued to evolve. The Greeks introduced the “polis,” a unique concept where the city-state functioned as both a physical space and a political entity.

- Roman Engineering Marvels: The Roman Empire established a vast network of interconnected cities, facilitated by their remarkable engineering feats. Roads, aqueducts, and a standardized administrative system ensured efficient communication and resource movement across their extensive territory.

- The Middle Ages and the Fortified Landscape: The feudal system prevalent during the Middle Ages heavily influenced settlement patterns. Castles provided a focal point, with smaller settlements clustered around them for both defensive purposes and access to the lord’s protection. Monasteries also served as centers of learning and religious life, attracting populations seeking spiritual guidance and economic opportunities.

The Modern Era: Industrialization, Urbanization, and Beyond (18th Century onwards)

- The Industrial Revolution and Urban Explosion: The 18th century’s Industrial Revolution significantly transformed settlements. Cities became magnets for populations seeking employment in newly established factories. London, Paris, and New York emerged as major metropolises, facing unprecedented challenges like overcrowding, inadequate sanitation, and inefficient infrastructure.

- The 20th Century and the Dawn of Megapolises: The 20th century witnessed the rise of the “megalopolis,” vast urban regions with populations exceeding 10 million. Technological advancements further fueled this growth, with efficient transportation networks and communication systems enabling the rapid movement of goods, services, and people.

The 21st Century and the Future of Human Settlements:

- Smart Cities and Sustainability: The digital age has ushered in the concept of “smart cities.” These urban centres utilize technology like sensors and data analytics to optimize resource management, improve infrastructure efficiency, and promote sustainability.

- Addressing Global Challenges: As the world’s population continues to grow, especially in urban areas, ensuring sustainable living conditions and addressing challenges like climate change remain crucial aspects of settlement development in the 21st century.

Classification of settlements

Based on Size and Population:

- Hamlets: Small, rural settlements with a population typically below 100.

- Villages: Larger than hamlets, with populations ranging from 100 to a few thousand. They often have basic amenities like shops and schools.

- Towns: More significant settlements with populations in the range of thousands to tens of thousands. They typically have a wider range of services and businesses compared to villages.

- Cities: Large urban centers with populations exceeding tens of thousands, often reaching millions. They offer a diverse range of economic activities, services, and cultural institutions.

- Megalopolises: Vast urban regions with populations exceeding 10 million. These are formed through the merging of several cities and surrounding areas.

Based on Location and Pattern:

- Nucleated Settlements: Compact settlements with buildings clustered closely together, often around a central point like a marketplace or public square.

- Dispersed Settlements: Houses scattered over a wider area, often seen in rural settings where people rely on agriculture or other land-based activities.

- Linear Settlements: Developments situated along a transportation route like a road, river, or coastline.

Based on Function:

- Rural Settlements: Primarily focused on agriculture, fishing, or forestry.

- Urban Settlements: Centers of economic activity, trade, administration, and cultural life.

- Resource Towns: Settlements established near specific resources like mining sites or oil fields.

- Resort Towns: Settlements primarily catering to tourism and leisure activities.