We live on a planet where water is ubiquitous. It covers 70% of the Earth’s surface and is responsible for 50% of the oxygen production on our planet.

Even though we know of more than one ocean, they essentially function as one huge body of water. Both the salt/ocean water (97%) and the freshwater (03%) work as a single mechanism to sustain life on Earth, hence the title ‘One Planet, One Ocean’.

Oceans are huge heat sinks that balance life on the planet. Our oceans are home to the Earth’s majority of biodiversity and are the main protein source for more than a billion people. It is estimated that around 40 million people will be employed by ocean-based industries by 2030.

Despite such an abundance of ocean water, it is a thing of concern, as around 90% of big fish populations have been depleted, and 50% of coral reefs have been destroyed.

Earth’s environment and climate are ultimately the results of stability provided by the oceans. Due to the complex and often less-understood mechanisms of oceans, the scientific community is deeply concerned about ocean health. This concern was pronounced when 8th June was declared World Ocean Day in 1992 in Rio de Janeiro at a parallel UNCED event.

Goal 14

Ocean health is one of the goals of SDGs or the Sustainable Development Goals set up by the United Nations General Assembly in 2005. Goal number 14 is ‘Life below water’, intended to be achieved by 2030.

What do we know about the oceans?

The short answer is, not much!

When we think about the ocean, three words instantly pop out: ‘Vast, Mysterious & Adventurous‘.

If we want to understand the relationship between oceans and human civilisation, then we should start with literary works. Most adventure movies, novels, and animations revolve around the tempestuous, serene, and hypnotic water bodies.

Humans are fascinated by this mystic and ungovernable entity called the ocean. An entity that cannot be fathomed by our most modern instruments. A territory not demarcated by our frontiers and borders. This fascination is a product of our illiteracy as our mind will imagine what it cannot see.

“Our biggest threat to the ocean is our ignorance of it,”

Margaret Leinen

We have reached the moon and Mars and have managed to touch the outer limits of our solar system. It is a remarkable achievement made by humans. But when we find out that ‘dark matter‘ exists, we realise that we have just begun to unwrap the most exotic yet ubiquitous matter known, or should I say unknown to man. The same can be said for our oceans, of which we know only a fraction. We know more about the surface of the moon and Mars than we know about the surface of our oceans.

What is ocean literacy?

‘With humility comes wisdom…’

Proverbs

We have to start somewhere to save our oceans, and the best place to start is by accepting that we know little about them.

Ocean literacy is the understanding of the ocean’s influence on you—and your influence on the ocean. It is a framework for understanding the vital role the ocean plays in sustaining life on Earth and the ways human activities impact it.

- An Ocean-Literate Person:

- Can understand the Essential Principles and Fundamental Concepts about the ocean.

- Can effectively communicate about the ocean in a meaningful and informed way.

- Can make informed and responsible decisions about the ocean and its resources.

Ocean literacy is essential for promoting sustainable practices, protecting marine ecosystems, and ensuring the long-term health of our planet. It empowers individuals and communities to act as stewards of the ocean, fostering a deeper connection and responsibility toward its preservation.

Who Is Involved in the Ocean Literacy Project?

The Ocean Literacy Project is a collaborative effort involving diverse stakeholders from various sectors. Key participants include:

- Scientists and Researchers:

- Marine biologists, oceanographers, and environmental scientists contribute knowledge about the ocean’s systems and their relationship with Earth’s processes.

- Educators and Schools:

- Teachers at all levels, especially those following frameworks like the Next Generation Science Standards (NGSS) and the Ocean Literacy Guide, help integrate ocean science into curricula.

- Government Agencies:

- Organisations such as the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) and other national or regional environmental agencies support ocean literacy initiatives.

- Non-Governmental Organisations (NGOs):

- Groups like the Ocean Literacy Network and various marine conservation organisations actively promote education, outreach, and advocacy.

- United Nations and Global Initiatives:

- The UN Decade of Ocean Science for Sustainable Development (2021–2030) highlights ocean literacy as a key activity for fostering global awareness and action.

- Community Groups and Individuals:

- Local communities, citizen scientists, and volunteers contribute by participating in projects like coastal clean-ups, habitat restoration, and public education events.

- Media and Communication Experts:

- Filmmakers, journalists, and digital media creators play a critical role in disseminating ocean literacy concepts to a wider audience through documentaries, articles, and social media.

- Industry Stakeholders:

- Sustainable fishing, shipping, tourism, and renewable energy industries collaborate to promote responsible ocean use and stewardship.

First things first!

How many oceans are there?

The straightforward answer is that there are five oceans. Traditionally, there were four recognised oceans: the Atlantic, Pacific, Indian, and Arctic. However, many nations, including the United States, acknowledge the Southern (or Antarctic) Ocean as the fifth. The Pacific, Atlantic, and Indian Oceans are the most well-known, while the Southern Ocean was the most recently designated.

In the context of “One Planet, One Ocean,” the five named oceans are not separate entities but part of a single, interconnected global ocean system. This concept underscores the idea that all oceans are interconnected, sharing water, ecosystems, and influences on Earth’s climate and life systems.

While we may label different regions for geographical and cultural understanding, the ocean functions as one continuous body of water, driven by global currents, tides, and exchanges of heat, carbon, and nutrients. This interconnectedness highlights the importance of understanding and protecting the ocean as a whole, as actions in one part of the ocean can have ripple effects across the globe.

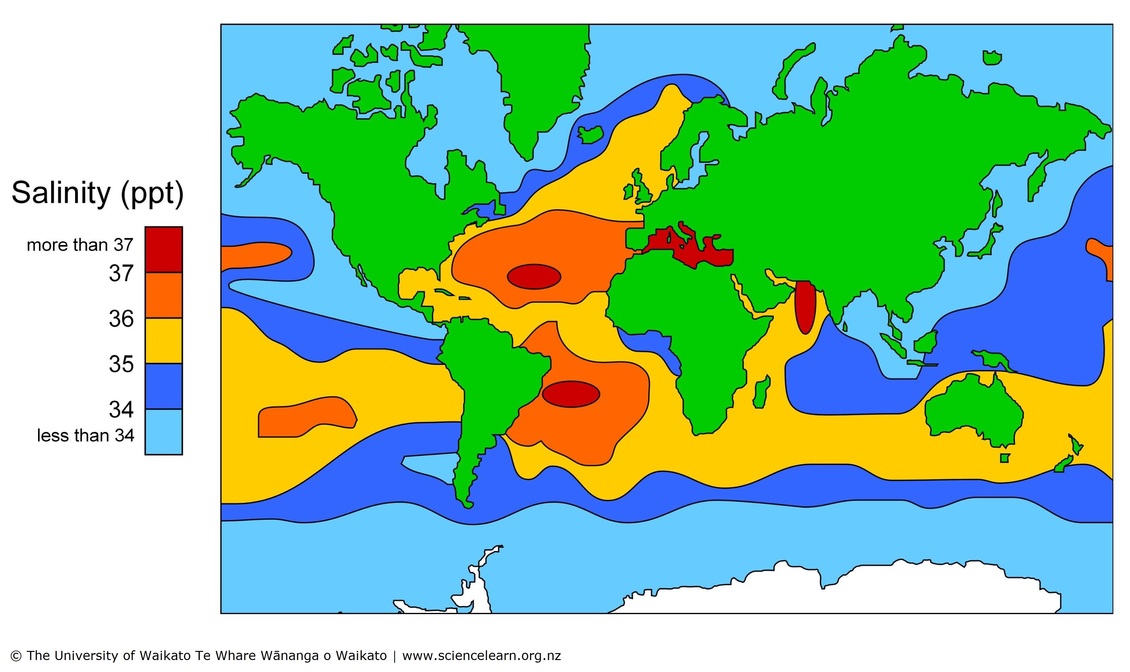

One big ocean with many features

Ocean water is a unique blend of water and dissolved substances. The average salinity is 35 parts per thousand (ppt), meaning that 3.5% of the ocean’s weight comes from dissolved salts. Chloride and sodium are the most abundant ions, followed by sulfate, magnesium, calcium, and potassium. Salinity varies across regions; for instance, the Dead Sea has an extreme salinity of 280 ppt, while minor variations, such as those between El Niño and La Niña years, are about 1 ppt. These variations significantly influence water density and marine ecosystems.

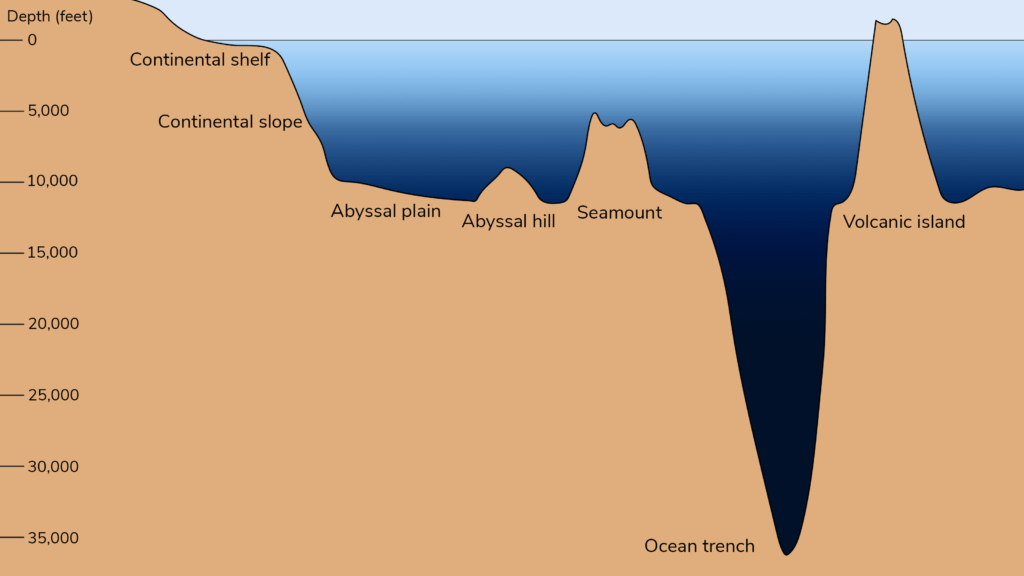

The ocean floor features diverse geographic structures, including continental shelves, deep-sea trenches like the Challenger Deep in the Mariana Trench, mid-ocean ridges, islands, and coral reefs. These features provide habitats for marine life and hold geological resources such as minerals and hydrocarbons. Upwelling zones, where cold, nutrient-rich waters rise to the surface, support abundant marine biodiversity and sustain major fisheries, like those off the coast of Peru.

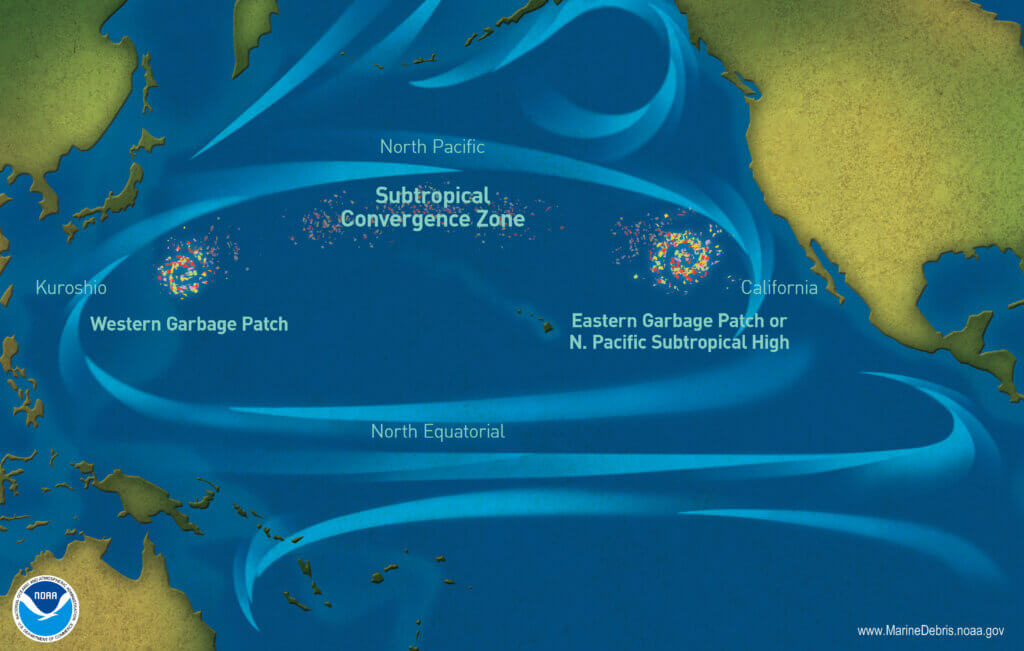

Ocean water is constantly in motion due to winds, Earth’s rotation, and density differences. Surface currents, such as the Gulf Stream, transport heat and influence global weather patterns. Deep currents, driven by thermohaline circulation, act as a “global conveyor belt”. They move water between surface and deep layers, redistributing nutrients and regulating climate. Ocean gyres, large circular currents like the Pacific Gyre, circulate water but also trap debris, leading to phenomena such as the Great Pacific Garbage Patch, which contains millions of tons of plastic waste.

Ocean currents transport heat, balancing global temperatures, while the ocean’s vast surface area drives the water cycle. Warmer temperatures increase evaporation by 7% for every degree Celsius, intensifying rainfall and drought cycles. Changes in salinity, driven by evaporation and precipitation, affect water density and can alter major circulation patterns, further influencing the global climate.

Tides

The movement of oceans and tides is driven by a combination of gravitational forces, wind, and Earth’s rotation. Tides are caused by the gravitational pull of the Moon and the Sun. They result in the periodic rise and fall of sea levels, creating high and low tides.

Marine ecosystems reflect the ocean’s dynamic conditions. Phytoplankton blooms, often visible in nutrient-rich upwelling zones, form the foundation of the marine food web. Salinity and temperature variations create diverse habitats. From the relatively stable conditions in most of the ocean to extreme environments like the hypersaline Dead Sea, which is inhospitable to most marine life.

Human activities significantly impact the ocean. Plastic pollution, concentrated in gyres, harms marine ecosystems, with studies showing that up to 10% of fish contain microplastics. Overfishing threatens biodiversity, particularly in nutrient-rich regions. Climate change exacerbates these challenges, as rising temperatures alter evaporation, precipitation, and ocean currents, disrupting ecosystems and weather patterns.

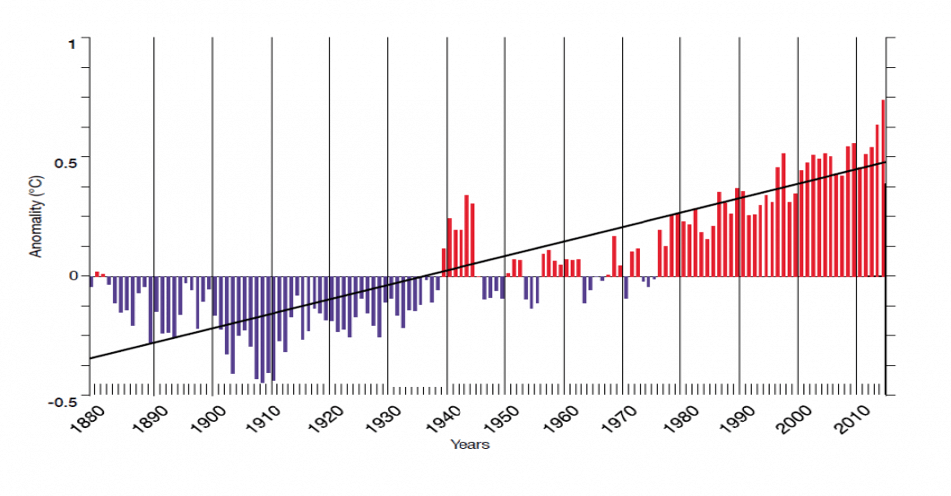

Massive Heat Sinks

The ocean serves as the largest solar energy collector on Earth, thus regulating the planet’s temperature. It can absorb vast amounts of heat from the sun without experiencing a significant increase in temperature due to its immense volume and heat capacity. This absorbed heat is distributed across the globe through the constant mixing of ocean water by waves, tides, and currents. These processes move heat from warmer to cooler regions, helping to balance temperatures across different latitudes and transferring warmth to deeper ocean layers.

The above image, sourced from NOAA, shows that the temperature of the upper few meters of the ocean has increased by approximately 0.13°C per decade over the past 100 years. This warming trend is evident in the temperature anomaly graph, also. It shows a consistent rise in global ocean temperatures, particularly from the mid-20th century onward. The red bars represent positive anomalies, indicating above-average temperatures, while the blue bars reflect cooler periods.

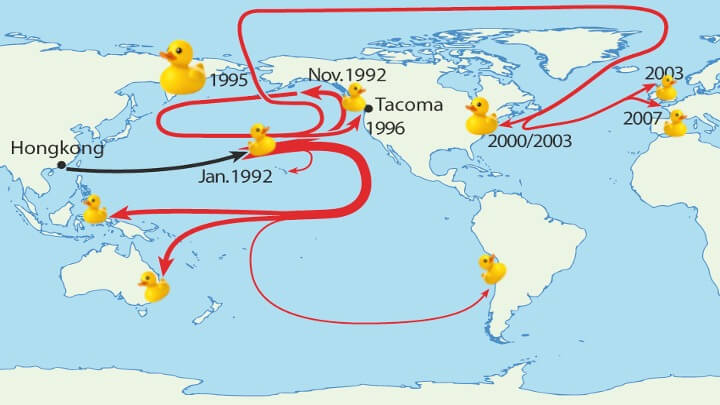

The ocean will transport everything

On January 10, 1992, a storm in the Pacific Ocean caused a freighter travelling from China to America to lose its cargo, which included 28,800 bath toys. This incident unexpectedly became an important study for oceanographers. The drifting toys helped scientists understand the interconnectedness of the world’s oceans. The bath toys floated across vast distances, carried by ocean currents. This provided valuable data on how objects and debris move across the sea throughout the globe.

The Great Garbage Patch

This interconnectedness of oceans gives rise to the catastrophe known as ‘The Great Pacific Garbage Patch’. It is the largest accumulation of marine debris in the world’s oceans. Located in the North Pacific Ocean, it lies between Hawaii and California, within a system of rotating ocean currents called the North Pacific Gyre. This area is often described as a “Plastic Soup” because it contains an estimated 7 million tons of waste, with plastic accounting for about 80% of the debris. The patch is massive—twice the size of Texas—and, in some places, up to 9 feet deep.

The garbage patch is not a solid mass but a concentration of microplastics, larger plastic debris, and discarded fishing gear. About 80% of the plastic originates from land, entering the ocean through rivers or being blown in by the wind. The remaining 20% comes from marine activities like fishing and shipping. Over time, sunlight and waves break larger plastic pieces into smaller fragments, making cleanup efforts even more challenging.

How has the Great Pacific Garbage Patch Formed?

The Great Pacific Garbage Patch forms due to the interaction of ocean currents, human activities, and the physical properties of plastic waste. It is located in the North Pacific Gyre, a system of rotating ocean currents driven by wind patterns and Earth’s rotation. These currents create a central area of calm waters where floating debris, primarily plastic, accumulates over time.

Plastics, being lightweight and durable, do not sink easily or degrade quickly. When plastic waste enters the ocean, it is carried by rivers, wind, and direct disposal into the sea. Once in the ocean, the debris is transported by currents, gradually converging in the gyre. Over time, a large concentration of waste builds up in this relatively stationary area, forming the garbage patch.

Economics of Oceans

The modern economy is dependent on the global ocean resources. The continental shelf, the submerged extension of a continent, is a region of immense economic and geopolitical importance. It is rich in natural resources, including oil, gas, and minerals, making it a focus of extensive exploration and extraction activities. Advances in technology have enabled deep drilling projects, allowing countries and companies to access valuable energy reserves from beneath the seabed.

The South China Sea is a hotspot for such activities and has become a theatre of geopolitical conflict. This region holds vast reserves of oil and natural gas and supports some of the world’s busiest shipping lanes. Several countries, including China, Vietnam, the Philippines, and Malaysia, claim overlapping parts of the sea, leading to disputes over territorial waters and resource rights. China’s expansive claims and its artificial island-building activities have intensified tensions, raising concerns about maritime sovereignty and freedom of navigation.

Similarly, the Arctic has emerged as a contested region due to its untapped reserves of oil, gas, and minerals. Melting ice caps, driven by climate change, are opening up new drilling opportunities and shipping routes, intensifying competition among Arctic nations, including the United States, Russia, Canada, and Norway. Russia’s aggressive Arctic strategies and the potential militarisation of the region have heightened tensions. The Arctic’s fragile ecosystem further complicates exploitation efforts, raising concerns about environmental risks and the impact on indigenous communities.

In conclusion

“One Planet, One Ocean: Spreading Ocean Literacy” emphasises the interconnectedness of Earth’s oceans and their role in sustaining life and economies worldwide. As we continue to rely on oceans for resources, energy, trade, and tourism, it is vital to understand the importance of ocean literacy—recognising the ocean’s influence on our daily lives and vice versa. From the rich ecosystems of the continental shelf to the strategic significance of disputed regions like the South China Sea and the Arctic, the oceans are central to both economic activities and geopolitical conflicts. To preserve the ocean’s health and ensure its resources are used responsibly, spreading ocean literacy is key. By spreading awareness and promoting sustainable practices, we can protect our oceans and ensure they continue to thrive, supporting life on Earth for generations to come.