The South China Sea dispute stands as one of the most complex and high-stakes geopolitical conflicts of the 21st century. Encompassing a vast maritime area rich in natural resources and crisscrossed by some of the world’s busiest shipping lanes, the region is claimed in whole or in part by multiple countries—each motivated by a potent mix of historical grievances, strategic calculations, and economic ambitions. At the heart of the dispute is China’s expansive “nine-dash line” claim, which overlaps with the Exclusive Economic Zones (EEZs) of several Southeast Asian nations, leading to growing friction over territorial sovereignty, resource rights, and freedom of navigation.

Beyond the regional players, the South China Sea has also drawn in global powers due to its critical importance to international trade and energy flows. An estimated one-third of global maritime commerce—worth over $5 trillion annually—passes through these waters. The area is also believed to contain billions of barrels of oil and trillions of cubic feet of natural gas, making it a flashpoint not only for military confrontation but also for economic competition. Despite diplomatic overtures and legal mechanisms, such as the 2016 arbitration ruling by the Permanent Court of Arbitration in favour of the Philippines, the dispute remains unresolved and continues to escalate.

What is the Nine-Dash Line?

The nine-dash line is a demarcation line used by the People’s Republic of China (PRC) to assert its expansive maritime and territorial claims over nearly the entire South China Sea. It is a U-shaped boundary made up of nine segments that stretch far beyond China’s mainland coast, extending deep into the Exclusive Economic Zones (EEZs) of other Southeast Asian countries like Vietnam, the Philippines, Malaysia, and Brunei.

UNCLOS vs. Nine-Dash Line

The conflict between UNCLOS and the Nine-Dash Line is a clash between a globally recognised legal framework for the world’s oceans and a unilateral, historical claim made by a single nation. UNCLOS defines maritime rights based on geography and internationally agreed-upon rules, while the Nine-Dash Line represents China’s claim based on contested historical precedent. This clash is the primary driver of the disputes in the South China Sea.

The United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), adopted in 1982, is often called the “constitution for the oceans.” It is a comprehensive international treaty that establishes a legal framework for all marine and maritime activities. 168 countries, including the People’s Republic of China, have ratified it.

| Feature | UNCLOS (United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea) | Nine-Dash Line |

| Basis of Claim | Geography. Based on a country’s coastline. | History. Based on China’s contested historical usage. |

| Nature | International Law. A binding treaty ratified by 168 parties. | Unilateral Claim. A claim made by one nation (China). |

| Clarity | Precise. Defines specific zones (12 nm, 200 nm) with clear rules. | Ambiguous. Vague line with no official coordinates or clear meaning. |

| Legal Status | The accepted law of the sea. China is a signatory. | No legal basis under international law. Rejected by a 2016 arbitral ruling. |

| Resource Rights | Grants exclusive rights to resources within a 200 nm EEZ. | Asserts rights to resources across nearly the entire South China Sea. |

Main Claimants and Their Positions

The territorial disputes revolve around overlapping sovereignty claims over islands, reefs, and waters in the South China Sea. The key claimants are:

| Country/Territory | Claims and Basis | Key Disputed Areas |

|---|---|---|

| China (PRC) | Claims ~90% of the South China Sea via the “nine-dash line” based on historical usage and ancient maps. | Spratly Islands, Paracel Islands, Scarborough Shoal, various reefs and shoals |

| Vietnam | Cites historical occupation and legal succession from colonial France. | Paracel Islands, Spratly Islands |

| Philippines | Maintains the same claims as PRC; original publisher of the 1947 eleven-dash line map. | Scarborough Shoal, Spratly Islands (Kalayaan Group) |

| Malaysia | Claims parts of the southern Spratly Islands based on proximity and continental shelf rights. | Southern Spratly Islands |

| Brunei | Claims maritime zones under UNCLOS without asserting sovereignty over islands. | Waters north of the Natuna Islands (not island claimant) |

| Taiwan (ROC) | EEZ zone overlapping the southern Spratlys | Paracel Islands, Spratly Islands, Scarborough Shoal |

| Indonesia | Rejects China’s claims near the Natuna Islands; refers to the area as the “North Natuna Sea.” | Waters north of the Natuna Islands (not an island claimant) |

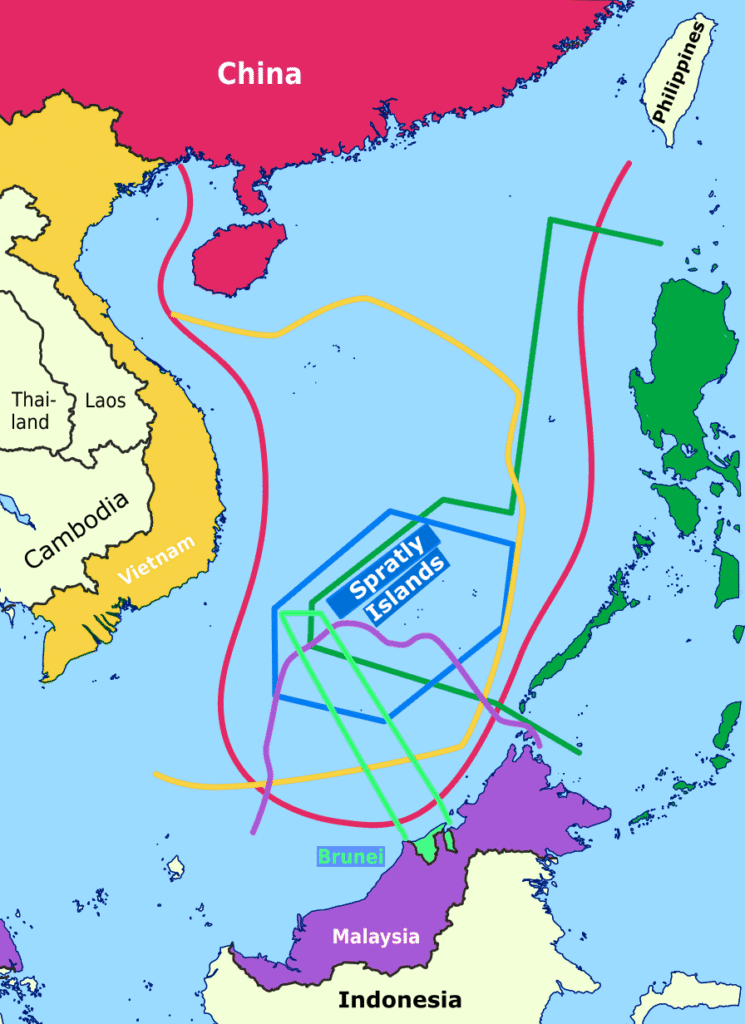

This map details the web of competing claims in the South China Sea, highlighting the conflict between international law and historical assertions. The colored lines represent the maximalist territorial claims of surrounding nations: China’s expansive “nine-dash line” (red), Vietnam (yellow), the Philippines (green), Malaysia (dark green), and Brunei (purple). These claims, many based on the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), create a geopolitical flashpoint as they overlap with China’s broad historic claim, which is not recognised under international law. All claims converge on the strategically vital Spratly Islands (blue polygon), an archipelago of over 100 islets and reefs.

Strategic and Geopolitical Importance of Shipping Routes

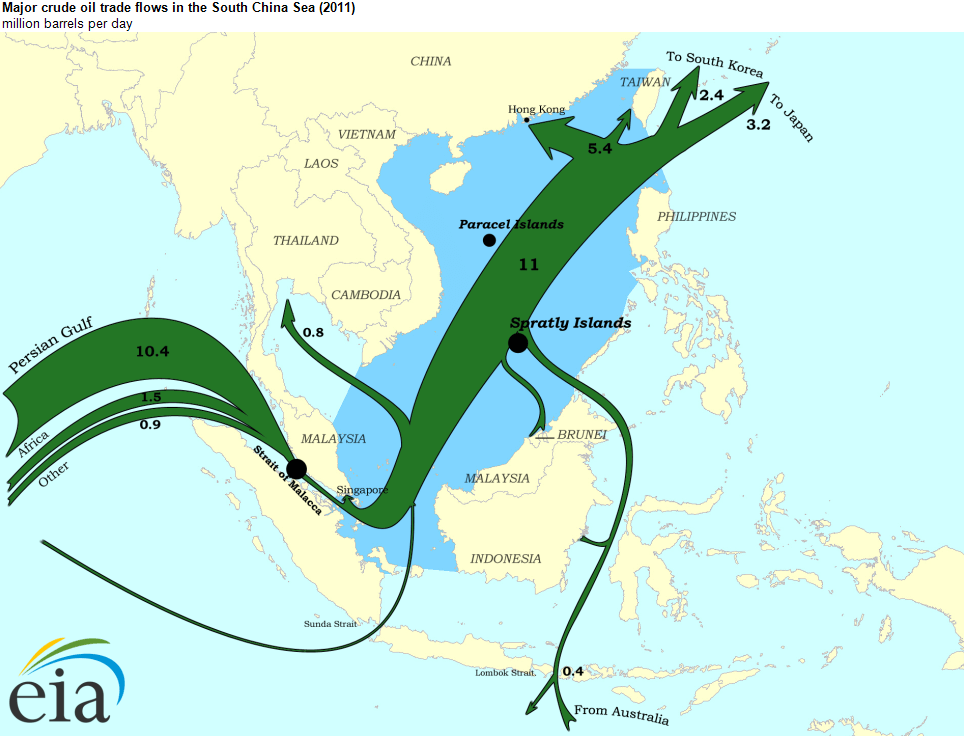

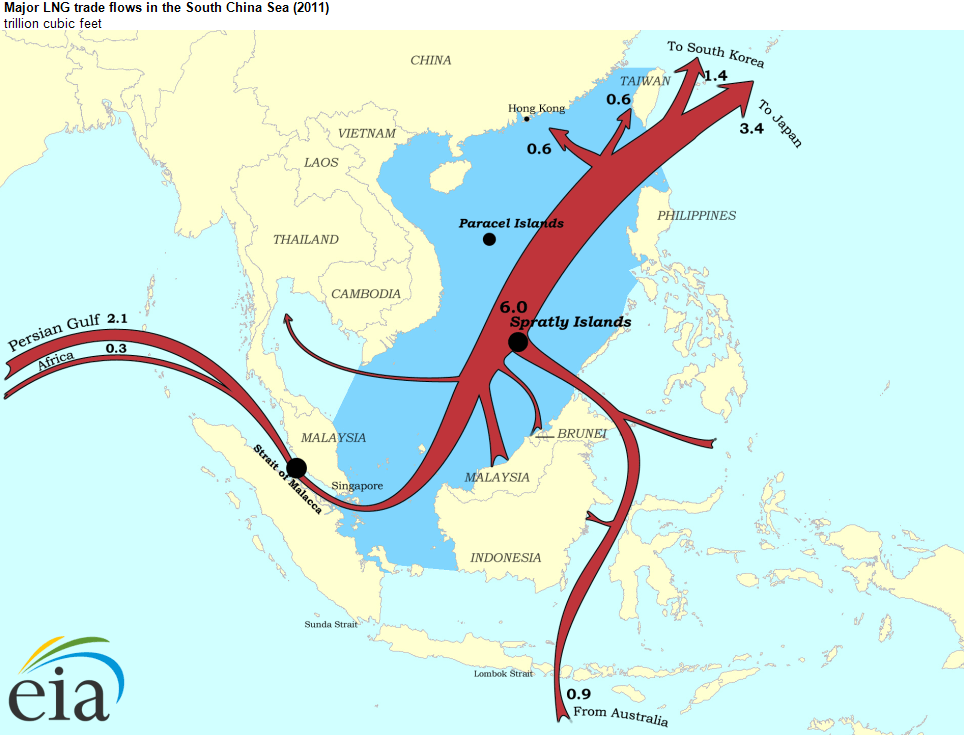

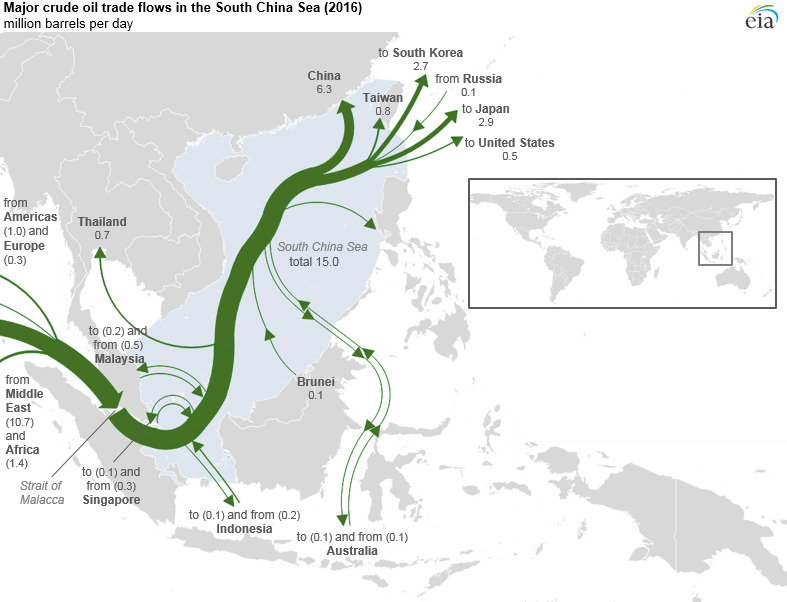

The South China Sea’s strategic and geopolitical importance is immense, primarily functioning as a critical artery for global maritime trade. An estimated $5.3 trillion in commercial goods, representing nearly a third of all global maritime trade, passes through these waters annually. Its significance as an energy corridor is even more pronounced, with approximately 30% of the world’s crude oil and 40% of its liquified natural gas (LNG) transiting the region through vital chokepoints like the Strait of Malacca, the Sunda and Lombok Straits, and the Luzon Strait. The economic security of numerous nations is therefore inextricably linked to the stability of these sea lanes. China, for instance, relies on the route for about 60% of its seaborne trade, while industrial powerhouses Japan and South Korea see between 40% and 90% of their essential commodities pass through. Similarly, around 55% of India’s trade utilises the Strait of Malacca, and the ASEAN states are fundamentally dependent on this regional trade network. Consequently, the ability to influence or control these sea lanes offers profound strategic leverage, serving as a primary motivation for China’s assertive maritime expansion and the corresponding geopolitical anxieties of its neighbours.

Natural Resources: Fueling the Dispute

The intense territorial disputes in the South China Sea are further fueled by the vast natural resources believed to lie beneath its surface. The seabed is considered rich in hydrocarbons, with conservative estimates from the U.S. Energy Information Administration suggesting at least 11 billion barrels of oil and 190 trillion cubic feet of natural gas. The U.S. Geological Survey indicates the potential for an additional 12 billion barrels and 160 trillion cubic feet in undiscovered reserves. Chinese national claims are far more optimistic, suggesting a potential wealth that, while largely unproven, creates a powerful incentive for asserting control over key zones. Beyond energy, the sea is a vital source of sustenance and livelihoods. Its fisheries support an estimated 3.7 million people, but this critical resource is in crisis, with fish stocks having plummeted by 70-95% since the 1950s. This scarcity has weaponised the industry, with militarised fishing fleets—especially those from China—escalating tensions through aggressive patrolling and harassment of vessels from other nations. Finally, looking toward future industries, the region holds long-term strategic value in its mineral wealth, including placer deposits of tin, gold, and chromite, as well as the potential for undersea Rare Earth Elements (REEs) and manganese nodules critical for high-tech manufacturing. This fierce, multi-layered competition for resources—from immediate food security to long-term energy and technological dominance—is a core driver of the region’s geopolitical instability.

China’s Artificial Island Construction and Militarisation

Beginning around 2013, China executed an unprecedented campaign of artificial island construction in the South China Sea, primarily in the Spratly Islands. Through large-scale dredging, it transformed submerged reefs and low-tide elevations—such as Mischief Reef, Subi Reef, and Fiery Cross Reef—into massive new landmasses capable of supporting significant infrastructure. These were not civilian projects; they were rapidly developed into sophisticated military outposts. China has since equipped these islands with military-grade runways over 3,000 meters long, reinforced aircraft hangars, deep-water ports, advanced radar and communications arrays, and defensive weaponry including anti-ship and surface-to-air missile systems. This network of fortified bases allows China to project military power across the entirety of the South China Sea, monitor regional activity, and create irreversible “facts on the ground” to enforce its territorial claims.

The 2016 Arbitration Ruling

In a direct legal challenge to China’s expansive claims, an arbitral tribunal constituted under the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) delivered a landmark ruling on July 12, 2016. The case, brought by the Philippines, sought clarification on maritime rights and the legality of China’s actions. The tribunal ruled decisively in favour of the Philippines, finding no legal basis for China’s “Nine-Dash Line” and its associated claims to “historic rights” within that boundary. Critically, the ruling also clarified that many of the features China had occupied and built upon in the Spratlys were legally defined as “rocks” or “low-tide elevations” and were therefore not entitled to generate their own 200-nautical-mile Exclusive Economic Zones. China, which had refused to participate in the proceedings from the outset, immediately rejected the legally binding ruling as “null and void” and has since refused to comply, creating a fundamental and ongoing conflict between the definitive judgment of international law and China’s continued assertions of sovereignty.

Current Situation and Future Outlook

As of mid-2025, the South China Sea remains one of the world’s most critical and volatile geopolitical flashpoints, locked in a state of precarious equilibrium. The dispute has evolved from a complex legal and territorial issue into a direct and enduring contest between two fundamentally opposed worldviews: the rules-based international order enshrined in the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), and a revisionist, power-based approach rooted in China’s expansive historical claims, embodied by the “Nine-Dash Line.”

The legal ambiguity has been settled since the 2016 Permanent Court of Arbitration ruling, which unequivocally invalidated the legal basis of the Nine-Dash Line. However, the practical reality on the water tells a different story. The situation is now defined by China’s persistent and increasingly assertive “gray-zone” campaign. This involves the relentless use of its powerful coast guard and a vast maritime militia to enforce its claims through intimidation and coercion, stopping just short of acts that would constitute open war. Incidents of harassment, the use of water cannons against Philippine vessels, dangerous manoeuvring near contested features like the Second Thomas Shoal and Scarborough Shoal, and the shadowing of other nations’ resource exploration activities have become routine. This calculated strategy aims to normalise Chinese control and gradually push other claimants out of disputed waters, creating a de facto reality that international law cannot reverse.